The Joy of the Wasteland

Hello. My name’s Daniel Kalder. I am the author of LOST COSMONAUT, a blackly humorous ‘anti-travel’ book about my wanderings in four surreal (but real) wastelands. It also contains a manifesto for Anti-tourism, which you can read at my website www.danielkalder.com. Over the next five days I’ll be contributing daily dispatches to Powell’s about Russia, Scotland, Central Asia and America, where I am currently residing after 10 years in Moscow. First however, I want to discuss the joy of the wasteland, which is a major theme in everything I do. Today I’m going to talk about three formative wastelands I have encountered; those that opened up the possibilities of the white zones on the map to me. So without further ado:

1) The Necropolis (Glasgow, Scotland)

I was born and grew up in Scotland during a period of sustained industrial decline. This has since turned into sustained population decline, as each passing year more people die than are born in my homeland. Immigration from Eastern Europe can massage the figures only so far: soon the Scots will be extinct, living on as a legend of a mountain people whose men wore skirts. But I don’t mind. We will be more interesting that way—as a beautiful, half-remembered myth.

My favorite wasteland in Scotland is probably the Necropolis in Glasgow. This is a quite remarkable place—as the name suggests, it is an enormous graveyard, built on a hill practically in the centre of town. Everything in the former second city of the British Empire radiates outwards from this locus of death. At the top there is a monument to the Scottish protestant reformer John Knox, a great enemy of ‘Popery’ who was delighted to see the Catholic Cathedrals of Scotland razed to the ground and/or stripped of their gold and jewels and other finery.

When I was a student, I would take my dates to the Necropolis. This was quite a trek, as I lived fifty miles away and couldn’t drive. So we had to ride the bus with the football hooligans and pensioners from the local villages. But I didn’t care. What could be more romantic than traipsing through the crumbling Victorian mausoleums, peering in through the iron gates at the discarded needles and blankets of the junkies who inhabited the Necropolis at night? And then afterwards, what would be more conducive to the blossoming of young love than a stroll around one of Glasgow’s many impoverished residential districts, where the locals staggered around, bombed out of their skulls on ‘jellies’*, chibs** at the ready to slash the face of anyone who might insult their honor by, for example, looking at them?

Rather a lot actually. This approach never got me to the second date. I had to change tactics, and conceal my love of decay and social disintegration for several years.

* Narcotic substance extracted from sleeping pills

** A Stanley knife

2) Chess City (Kalmykia, Russia)

Flash forward. I had been living in Moscow for a long time and with my friend Joe had done a lot of traveling in Russia. We had seen more onion domes than Michael Jackson has had pajama parties. We wanted to go further—so we started picking places with weird names off the map at random, places that we couldn’t picture in our imaginations—then we’d buy train tickets out there and voyage into the void. That was how we wound up in Kalmykia, a semi-autonomous republic in Southern Russia. Kalmykia is fascinating for several reasons: not only does it contain the only desert in Europe, but it is also homeland to a group of stranded Mongols, ruled over by the eccentric Kirsan Iliumzhinov. Iliumzhinov is a businessman, author and mystic: he claims to have been abducted by aliens. Fortunately the aliens didn’t probe him in any personal places; on the contrary, they treated him well, as befits a leader of his dignity and stature. He is also a chess fanatic, and is president of the World Chess Federation.

Joe and I took a taxi from the capital, Elista, drove through some dust and concrete to the edge of the steppe, and went wandering in his ‘Chess City’, a futuristic complex of buildings built to host the 1998 Chess Olympiad. The most impressive structure was the Palace of Chess, a gleaming pyramid of marble and glass. Inside, however, it was abandoned: chess tables were set up for games that would never be played. There was a Museum where the guide blabbered manically at us, so long had it been since she had had contact with any living thing. But the strangest and most mystical vision therein was the photograph of Walker, Texas Ranger, Chuck Norris himself, staring at the foundation pit of the Palace, next to Ilumzhinov. What was Chuck doing there? This question has haunted me for close on four years now…

3) Dead Town (Texas, USA)

Did this town have a name? I cannot recall. But I am always looking for the shittiest town, the dirtiest hovel. Beautiful towns are all alike; a shit one is always shit in its own way. So not long after I arrived in America, I was excited when I passed through this forgotten zone in the car (I wasn’t driving, I still can’t drive). Everything was devastated: from the broken down Dr. Pepper sign at the entrance, to the collapsing wooden houses with ‘Beware of the Dog’ signs on them, to the general air of abandonment in the town centre. I saw humans on the street: broken, bowed humans, shuffling along, dragging their sadness behind them, or on their shoulders. Here they were, living in what is by far the richest country in the world, and yet they were sunk deep in poverty and despair. They were up to their waists in it, like a quicksand that took decades to swallow you. You don’t get out of that kind of quicksand. You can just move slowly about in it, a couple of millimeters at a time, as you sink slowly ever downward.

But the day I returned to walk around, there was nobody about. It was bizarre. Every shop was closed, barricaded, boarded up. There was a movie house, a restored Art Deco building from the earliest days of Silent Cinema, but it too was locked down that day. Nearby was a Church without worshippers. I walked south, to the Hotel Deadtown, but the windows were boarded over, the rooms full of silence. In the end I found a man living under a bridge. He wore jeans with stars on them. He spoke to me in the gibberish of a madman.

The enigma of Deadtown continued to haunt me, and a few weeks later, I returned. This time some of the shops were unboarded. I went within. Of course, they were dismal. It was as if the city was cannibalizing itself, and having sold off everything that was of any value, only the junk that remains when all the desirable and collectable fragments have been spirited away was left. There was a plastic cup with 1973 written on it; a spider was shitting in it. Other than that, only dust, scraps of cloth, broken toys and bits of dirty glass and metal were left. And yet there were humans walking about in there, rooting through the unreadable novels where the pages were glued together with human feces, trying on the clothes their neighbors had died in, clothes that still had the whiff of rotting flesh on them. I went from shop to shop drinking deep of the darkness.

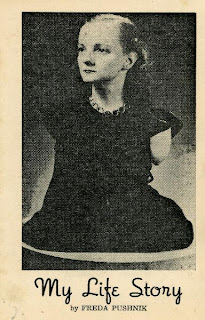

And then suddenly: magic. Amid a pile of old postcards that no-one could possibly want, I found this testament to the cruelty and beauty of the world:

And then suddenly: magic. Amid a pile of old postcards that no-one could possibly want, I found this testament to the cruelty and beauty of the world:

I come from the wasteland, I love the wasteland. Maybe that’s why I find myself returning so frequently—because, although the people living there are our brothers and sisters, no-one tells their stories. They are unseen, unknown, lost. I, however, am a proud member of the Tribe of the Invisible, and have come, as an emissary from amid their ranks, bearing darkness…

From Powells.com (16/10/06)