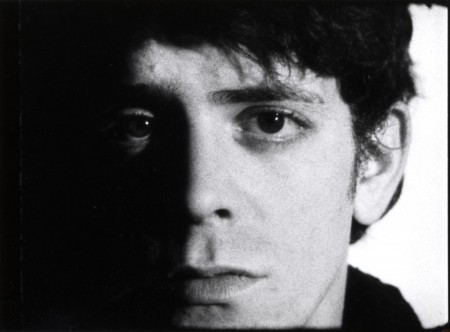

Vanishing Act: How Lou Reed Did Death

Although he may not have racked up the body count of a Nick Cave or Johnny Cash, the late Lou Reed sang about death more often than many a popular musician. Indeed, he did it often enough that what I originally thought would be a single piece examining how his approach to the subject of mortality mutated over his creative career has become a two-parter, of which this is the first. So let’s get down to business; the business of singing about death, that is.

The first track I can think of where Reed explicitly dealt with human perishability is “The Gift”, on the second Velvet Underground album, which was released in 1968 (I’m not counting the impressionistic ramblings on “Black Angel’s Death Song” from the previous year’s debut LP). Not really a song but rather a short story written by Reed and narrated by the greatest living Welshman over a throbbing bass line banged out by the same, “The Gift” tells the story of a chump who mails himself to his indifferent girlfriend. He then gets stabbed in the head when her friend opens the box with a sheet metal cutter. Reed was a young man then, a lad of 26, and in “The Gift” death appears as a macabre joke, a punch line that ends a sardonic tale about modern relationships: boom boom!

However five years later in 1973 and we find Reed, now aged 31, writing about both relationships and death in a much more intimate, disturbing and aggressively depressing way. The year before he had released the successful Transformer LP; co-producers David Bowie and Mick Ronson had added persuasive and even pretty glam makeovers to ambiguous songs such as “Perfect Day” and “Walk on the Wild Side”. So now the habitually antagonistic Reed decided to assault/horrify his new fans with Berlin, an ultra-downer of an album he recorded with producer Bob Ezrin, who had made a name for himself recording tongue-in-cheek bad taste songs about dead babies and necrophilia with Alice Cooper.

Berlin was as theatrical as anything Alice Cooper ever did, but it was a decadent, Weimar rock cabaret type of theatricality, informed by Ezrin’s skill at combining full-on orchestrations with avant-rock. Indeed, Reed was largely sidelined as a musician on the record, all electric guitar duties being handled by virtuoso session musicians; even the bass lines were laid down by Jack Bruce and future King Crimson prog titan Tony Levin.

But Ezrin also knew when to strip down the sound, to expose Reed’s stark lyrics for dramatic effect. Case in point: “The Bed”, a song in which Reed’s narrator quietly contemplates the bed he shared with a woman he loved, the bed where their children were conceived, which is also the bed where she cut her wrists one alternately odd and strange “fateful night.” And yet, as he remarks with a chilling callousness: “I never would have started if I had known that it would end this way/But funny thing, I’m not at all sad that it stopped this way.” The detachment which manifested itself in the jocular tone of “The Gift” had become something eerie and disembodied. There is no body, no blood, only an empty bed:

Berlin tanked, and Reed followed it up with a few more commercial records, before reverting to combative type and assaulting his fans and record label alike with the not very listenable double LP of guitar feedback noise Metal Machine Music. By 1978 he was writing songs again although Reed, now aged 35, was getting on in rock star years by the standards of the era. Written in a semi-punk vein by a progenitor of the movement (less convincing disco dabbling would follow a year later), Street Hassle is a solid album, and it contains one of the best tracks Reed ever recorded—the three part title suite about love, sex and death.

“Street Hassle” is written from several different perspectives. In part one, Reed sings about an encounter between (likely) a drag queen and a male prostitute culminating in a fairly earth-shaking sexual experience, before cutting abruptly in part two to a room where a woman is lying dead from a drug overdose. The voice alternates between faux sympathy for her partner and utter disdain: Hey that c**** not breathing/I think she’s had too much/Of something or other, hey man you know what I mean?

Reed’s narrator is again detached, but whereas in the previous two songs the body was unseen, or even absent, now the corpse is the object of the song, and viewed with extreme distaste as dead meat, a nuisance, a bummer, a buzzkill that could cause problems with the cops. Irritated, the narrator advises the (presumably traumatized) man to take his “old lady” and dump her in street. I can’t think of another song where a dead body is spoken of with such cold, disparaging disregard. Reed cuts to the chase with this line:

When someone turns that blue you just know it’s a universal truth that that bitch will never f*** again

And then Bruce Springsteen starts mumbling.

The onset of early middle age brought about radical changes in Lou Reed’s personal life and in his music. Whereas he had spent much of the 70s living with a Brazilian transsexual named Rachel and maintaining his reputation as a drug-addled denizen of New York’s demimonde, in 1980 he got married to a designer named Sylvia Morales and seemed to have consigned his bisexuality and rampant drug consumption to the past. By 1982 he was proclaiming “I love women” to the world, in a fairly terrible song recorded for The Blue Mask. By 1984 he was in a very good mood indeed, and released the most upbeat recording of his long career, New Sensations.

Exceedingly poppy by Reed’s standards, New Sensations definitely sounds like a record made by a middle aged rocker hoping for some hits and an infusion of cash. It features the processed, tinny, crashing drum sound that marred many a pop song in the 80s, and yet Reed does not go full cheese as his peers Mick Jagger and David Bowie would at the same time. In fact, I really like New Sensations: Reed mixes confessional lyrics about struggling with his darker side into the love songs, dabbles in satire on a track about playing video games, sings convincingly about having a pleasant night out in the city, and also turns in a song track about having an awfully good time on his motorbike.

On side 2 however he does death again, in a song entitled “Fly into the Sun.” It was the height of the Cold War and filmmakers and even Frankie goes to Hollywood were churning out depressing stuff about mutually assured destruction and slow death by radiation. But Reed just wasn’t feeling that down about global death by nuclear fire. In fact, he rather liked the idea.

Thus at age 42 Reed recorded the first song in which he contemplated his own mortality directly in the first person, and not only the possibility of his death but everyone else’s, striking a remarkably cheerful note as he mused upon the annihilation of our species, the earth and the stars: I would not run from the holocaust/I would not run from the bomb/I’d welcome the chance to meet my maker and fly into the sun/fly into the sun/fly into the sun/I’d break up into a million pieces and fly into the sun

Indeed, this kind of death is something to look forward to; Reed describes it as a blessing, a relief not only from “worldly pain” but also as providing an answer to the “mystery,” as if he found pondering existence something of a drag. The central image is of being embraced by an extinguishing light, and disappearing: to cease to exist is liberation, death in a global cataclysm is “a wondrous moment,” an opportunity even—“I’d shine by the light of the unknown moment and fly into the sun”

Of course, there’s something very abstract about looking at death this way. Is the prospect of global extinction really so awesome? Or perhaps, beneath the upbeat poppy melodies, there lurked a profound undercurrent of ennui, and a desire to disappear, to vanish, to cease to be. But Reed had a good three decades left to go before he would reach that point. And in the meantime, he still had a lot of singing to do about death, as we shall find out in part two…

The Dabbler, November 2013