An Interview With Mikhail Shishkin

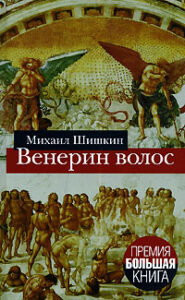

Mikhail Shishkin made his literary debut in 1993 and swiftly went on to win acclaim as one of the greatest living contemporary Russian writers. He is the first author to win all three of the major Russian literary prizes—the Russian Booker, the Big Book Award, and the National Bestseller Award—while his work has been translated into twenty five languages. In fall 2012, Open Letter will publish his novel Maidenhair, in translation by Marian Schwartz; while in 2013 the British house Quercus will publish Letter-Bookin translation by Andrew Bromfield. In anticipation of his appearance at this year’s BEA, regular Publishing Perspectives contributor Daniel Kalder spoke to him about literature, exile and creating a new language.

Mikhail Shishkin made his literary debut in 1993 and swiftly went on to win acclaim as one of the greatest living contemporary Russian writers. He is the first author to win all three of the major Russian literary prizes—the Russian Booker, the Big Book Award, and the National Bestseller Award—while his work has been translated into twenty five languages. In fall 2012, Open Letter will publish his novel Maidenhair, in translation by Marian Schwartz; while in 2013 the British house Quercus will publish Letter-Bookin translation by Andrew Bromfield. In anticipation of his appearance at this year’s BEA, regular Publishing Perspectives contributor Daniel Kalder spoke to him about literature, exile and creating a new language.

You moved to Switzerland in 1995, when you were already in your mid thirties. Were you concerned that distance and detachment from Russia would alienate you from the language and subject matter? How did that “exile” affect you as a writer?

If you are over 30 you can’t learn anything new about your own country. It’s like a tree: every season it changes its appearance, but you know that this is the same tree. And even if the leaves would proclaim that they have changed the name of their native tree from “Soviet birch dictatorius“ to “Russian birch democraticus“ you know what shape of leaf will appear the next year: the same, actually.

I think it is very important for any writer from any country to live abroad for some years. This is the best way to understand yourself and your background. My “exile“ helped me to realize that I should not write about exotic Russian problems but rather about the “human being.“

You adhere to a grand and noble conception of literature, that it should have a serious moral/philosophical purpose, that indeed reading plays a role in “preserving human dignity”. How much of this is down to your soviet (or Russian) upbringing? Do you feel this attitude is generally dead in Russia today- the 90s were a period of post modern nihilism- or does the tradition continue?

When I was 16 reading saved me. I am afraid that you can’t really comprehend what it means to be born in the happiest country in the world and then realize that this is a huge prison and that they were all lying. I felt as though my country was occupied by invaders. The enemies could be in possession of my body but they could not capture my thoughts. What was inside my skull was a territory of my freedom in that prison. Reading forbidden books (and even Joyce and Nabokov were forbidden) was my fight. And the victory was mine.

Now I often go to Russia to meet my readers both in the “capitals“ and in small provincial towns- which is much more interesting and inspiring. There you can see that nothing has changed in the last 20 years: the real Russian readers—provincial teachers, doctors, librarians—still need some demanding books to save their human dignity in this everyday avalanche of humiliating “democratic“ reality. Communist lies have switched to “democratic“ ones. This literary tradition still works in Russia: writers write to save their souls and readers read to save theirs. Reading in Russia is more than reading. And it always will be.

Your work has won many prizes and much acclaim, but has your status as an “outsider” brought criticism? I lived in Russia for ten years and felt that in the 2000s the country became more closed, hostile to criticism, to external perspectives…

I was harshly criticized by our “new patriots“. The accusation was: “What moral right has a writer to write about Russia if he lives in Switzerland?“ But later, after all the prizes, my most severe critics wanted to become my friends and conduct interviews with me. You know critics are like suckerfish: they go with the ship. They always are filled with indignation that you are not going in the direction they’d like to go. But why should a ship care? It has its own destination.

Growing up in the USSR you thought your work would be un-publishable in the USSR and might only ever see print abroad. Was destiny always calling you to leave, to become a writer in semi-exile?

I started to write early and was sure that one day my texts—if they were really good and deserved publication—would appear abroad because it was impossible to publish my writing in the Soviet Union. Who could have imagined that three Soviet leaders in succession would “kick off“ in a period of just four years and leave the young and weak Gorbachev to save the regime. The last Communist leader failed, so my books were published in Moscow and after that all over the world. My latest novel “Pismovnik (Letter-Book)“ which will appear in English translation by Quercus in Great Britain has now been translated into 25 languages. By the way my “semi-exile“ was in no way politically motivated- it was just a family matter.

You stress the importance of tradition, and that you feel you are a part of a tradition. Are you speaking of the Russian literary tradition, or something broader?

There are only two traditions of writing whether you are Russian or not. The first one means earning money by writing what they expect from you. The writer as servant. And the other kind of writing I compare with a blood transfusion. A writer shares with his reader the stuff which is essential and vital for him. But of course the blood group must match. This tradition matters.

“Maidenhair” will be published by Open Letter this October. It’s a big, complex, challenging book that draws on your own experience as an interpreter for refugees, and which travels across time, and contains many voices. You have spent some time in the US—do you think American audiences are ready for it?

When “Maidenhair“ was first published in Moscow, the critics were distressed that such a great and demanding book would never reach a broad audience in contemporary Russia. The publisher of “Book Review“ magazine promised in his blog that he would “eat his underpants in public“ if this novel ever sold 50 000 copies. It is to be regretted that critics never keep their word. This amount of copies was sold in the first year and you shouldn’t forget that in Russia you can download all new books on the Internet for free. As for the Americans I think you should never underestimate readers, even in the US.

Do you think your experience living outside Russia somehow makes your books more readily accessible to non-Russians?

Yes, I think so. Several Russian generations in the 20th century spent their lifetime in jail. They developed their own way of thinking and speaking. The leakproof prison reality gave birth to a very special subculture. And Western readers cannot identify themselves with Russian exotica. It is time for writers to bring Russia back to the world, as it was in the 19th century. Russian literature is worth it.

“I am creating a language of my own that will exist outside of time.” Are you succeeding?

If you don’t try to create such a language you are not a writer, but just a scribbler for sale. And as to who will succeed- we’ll know the answer in one hundred years’ time. Wait and see.

Originally published by Publishing Perspectives in June 2012 to coincide with the Read Russia Festival in NYC.